The Great Mystery is not to be Solved!

Carlos Castaneda applies a simple and elegant distinction to reality: He divides the field of action and awareness (the world) into two spheres — the known and the unknown, the right side and left — and associates corresponding practices with each. These practices are called stalking, the art of handling ordinary reality (the known) in non-ordinary ways; and dreaming, the art of entering and participating in the fluid and magical world of the unknown, the non-ordinary reality.

We’ve been taught that learning comes from thinking, study, analysis, and deliberation — the act of reasoning — and that knowledge holds the keys to power and will open doors to success. Our educational system promotes this primarily intellectual process, where neutral, non-participatory observers study separate and disconnected objects and events that make up the world. Applying scientific analysis and method to the challenges of physical existence has radically transformed the material, social, and psychic reality we live in. But mesmerized by the considerable powers of thought, we often substitute and confuse this disconnected and disembodied intellectual process with the process of life itself — “I think therefore I am.”

Castaneda’s system heads in another direction and leads to different conclusions than those taught in our schools and social institutions. In the magical and enchanted world of Castaneda and his cohorts, the depth, richness, and quality of your life has much more to do with the nature of your relationship to the unknown than how much you know in the world of ordinary, consensus reality. And a “man of knowledge,” or seer, is one who molds his character and refines his personal mastery in order to explore those fluid and magical landscapes outside the borders of the known.

Thinking is just one possible way to engage with the world, and our obsession with it ignores other whole domains of experience. As Carl Jung noted, the capacities of sensing, feeling, and intuitive imagination – generally not nurtured in modern life — are equal, but alternative modes of knowing. Rarely given anything close to the 12-16 years invested in schooling the mind, these other abilities can be developed, and they can open windows onto alternative vistas with different, but vast potential for learning, action, and engagement.

In addition, we spend a full third of our life sleeping. This non-waking consciousness contains the realm of dreams, whose forms of perception and relationship have very different rules than those of daily experience, and where wildly-creative landscapes and possibilities for action beckon from outside the house of reason. To ignore or discard this consciousness, to label it inferior to rational modes of thought or irrelevant to waking life is absurd and irrational in itself. Yet we do, and by treating flesh, emotion, and imagination like undesirables, our potential to live with depth and passion atrophies, and the resulting emotional and imaginative illiteracy sends our national dialogues into swamps of the boorish and banal.

These negative side-effects of how we’ve been taught to think are major, but not the whole picture. The most significant problem with our inherited approach to knowledge is simply that the unknown is vast — far greater than the known. Like the iceberg whose mass — ninety percent – lies invisibly below the water, our perceivable and knowable universe comprises a small segment of reality. The known world — like a boat adrift on an immense ocean – is a minor fragment of existence, and to focus our attention and keep our energy tethered within the confines of this little sphere is to live in a prison of our own making.

Neuroscientists say we use less than ten percent of our brains to create, sustain, and act within what we know. And we know so little. For all our focus on knowledge, we have no idea about the relationship between thinking and matter; how particles emerge from nothingness; or how desire gets translated into movement and action. Meanwhile, our relentless internal dialogues remove us from our bodies, emotions, and imagination; keeping us stuck in our heads and unaware of even the most basic realities like the quality of our breathing moment to moment; whether we feel angry, scared, or hungry; or the deeper callings of our souls.

Since the unknown is so vast compared to the known, all religions, philosophies, or forms of inquiry focused on or mired in the known will be limited at best, and foolish or dangerous at worst. We are taught and can try to be reasonable, but in fundamental ways we are not. Like a woman wanting to be a man or someone of color trying to be “white,” pretending to be what we’re not involves ignoring our roots, denying other, equally-rich heritages, and repressing large parts of who we are.

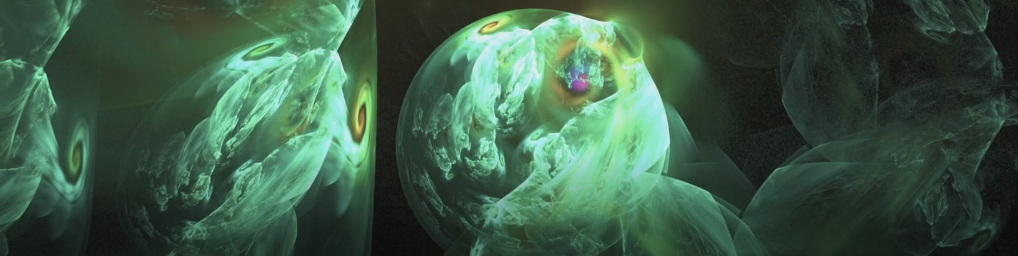

In the new worlds of quantum physics, the known is dissolving. Reality looks relative and relational. The quantum universe is probabilistic, a seething field of possibilities, and the old rock of reason has broken down into a shore of shifting sands. In this fluid landscape, there is no objective existence “out there.” Inner and outer meet, interact, and dance together. In this rhythmic duet, the perceiver’s intention, focus of attention, or lens looked through evokes and draws forth the emerging form of “reality” from the mysterious flux perceived to be outside in the world.

Primal cultures referred to the living presence of this “Unknown” as the Great Mystery. It was the source and origin of everything — all facts, shapes, forms, and expressions of existence — the wellspring out of which emerged all which could be experienced and known. The Great Mystery was a focus of reverence, the matrix and mother of our being-ness, the background and context within which we live, know, and perceive.

To experience the Great Mystery is to know God, the Source, our creator. To experience does not mean to think about or understand. To experience means to be intimate with. For millennia, developing a relationship of appreciation, gratitude, and respect with this Unknown was the primary task of life. Creating, nurturing, and sustaining this relationship led to a sense of belonging, finding one’s place in the universe, and having a home. To do so resulted in deep feelings of peace, and a feeling of wonder, purpose, and connectedness with all parts of creation.

Leave a Reply